<----- Click photo for

The Video Documentary

Click for images of "The Chimneys"

All that remains of the original Stafford slave quarters

A Stafford Family

Cumberland Island

Pilgrimage, 2006

NPS magazine presented “A Chance for Freedom,” an article by Mike Bezemek

Images from...

A portion of portrait titled "The Quarters"

Wild horses graze near Robert Stafford's gravesite

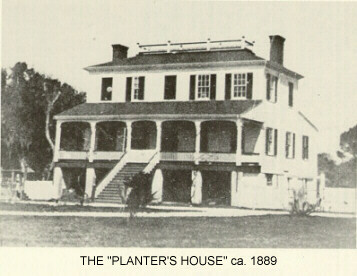

Robert Stafford's Home in 2006

Robert Stafford's Home around 1889

Many family members believe the evidence that points to Stafford Plantation on Cumberland Island, Georgia as a location of several of our ancestors before, during, and even after the Slave Emancipation era. This page and its links are presented to educate, inform and to preserve this cherished legacy.

Click to view the Stafford Family piece for...

Click the Image below to download the short video

Sometime in the 1830s, when Zabette was probably in her early twenties, Robert Stafford, the owner of the largest plantation on Cumberland Island and eventually one of the richest slave owners, employed Zabette as a nurse.

Stafford, and Zabette never married, but had a relationship that lasted in some fashion for over fifty years and resulted in six children.

The Stafford's of

- Cumberland Island -

an Ancestry & Information Site

Read a 2015 article on Stephen R. Stafford II, featured on:

IN THE Unites States the statistics for black males who are of school age are not that good to say the least:

• Black males are twice as likely to be held back in elementary school as white males

Black males are twice as likely to be held back in elementary school as white males

• Black males are three times as likely to be suspended from school

Black males are three times as likely to be suspended from school

• Only 50% of Black Males are likely to graduate from college.

Only 50% of Black Males are likely to graduate from college.

But Stephen R. Stafford II has very different statistics.

This is a 2021 article highlighting the story of Ned Simmons,

one of many enslaved black men of Cumberland Island,

who fought for freedom from slavery, alongside British military forces during the War of 1812.

Who Was Zabette?

"ZABETTE"

Ned Simmons and dozens of others were asked to line up on shore by their former owner. Until the middle of January of 1815, he’d been an enslaved carpenter at the Dungeness plantation on Cumberland Island, but Simmons and other enslaved laborers had jumped at the opportunity when British soldiers took over the island and offered them freedom. Now Louisa Greene Shaw, Dungeness’ owner, made a desperate attempt to convince them to change their minds. “She gave them a long talk,” a friend of the Shaw family wrote later. “Told them how kind they had been treated by all the family. All this had no effect.”

“The Chimney’s” in Augusta Chronicle news article

Painting shows how slaves lived on Cumberland

By Gordon Jackson | Morris News Service

Tuesday, January 17, 2006

ST. MARYS, Ga. - A new painting is educating visitors about a little-known slave community that once existed on Cumberland Island.

The painting, called The Quarters, accurately illustrates what a slave village near the Stafford Plantation on the island looked like in 1850, according to officials from the National Park Service. The painting is on display at the park service's visitor center in St. Marys

.

The artist, Martin Pate, of Newnan, was commissioned to create the painting using information from historical documents and records, an archaeological dig of the site, photographs of the ruins and a visit to the island.

The artist was not given a creative license to embellish on what the village looked like during the era depicted in the painting, said John Mitchell, the curator for the Cumberland Island National Seashore Museum in St. Marys.

"It's extraordinarily accurate," Mr. Mitchell said. "It gives you a view of the past." Nothing remains of the village, now called "The Chimneys," except the brick chimneys and fireplaces that were part of the wooden cabins occupied by slaves living on the island.

Few people see the ruins because the site is surrounded by private property and is about three miles from the dock where a ferry drops off tourists.

"This will draw attention to a part of the island people don't know much about," Mr. Mitchell said.

The painting would not have been possible without a partial archaeological dig of site in 1999, he said.

Brenda Barber, a former caretaker at the Stafford Mansion near the village site, said she was impressed with the detail and accuracy of the painting.

"It's pretty representative of the area," she said. Mr. Mitchell said the painting might be moved later to the Park Service museum, two blocks from the visitor center, and put on display with some of the artifacts unearthed at the site.

The artifacts include pipe stems, hand-painted marbles, fishing weights, a metal lice comb and an 1819 half-dollar.

A number of gun flints indicate the slaves had weapons to hunt. The dig uncovered buttons from military uniforms, which indicates slaves wore surplus uniforms as clothing.

From the Tuesday, January 17, 2006 printed edition of the Augusta Chronicle

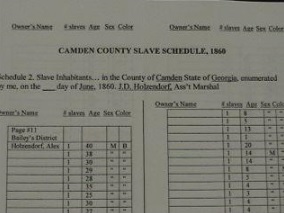

A 2006 photocopy of an original slave record with the names of enslaved persons who took on the name of "Stafford." These names match names found in our oral history records. Photo was taken at St. Marys office of Vital Statistics.